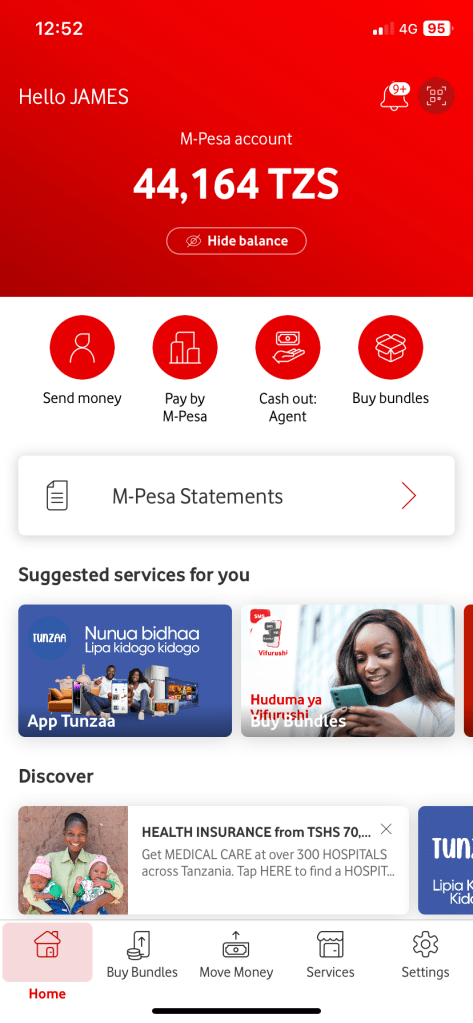

Recently a young woman from work called me at 8 pm on a Sunday night crying because her mother had just been rushed to the hospital needing immediate surgery. Jackie needed the equivalent of $200 CAN for the operation. There is no universal health care here and most people cannot afford private insurance. Usually insurance means friends, family and mzungus (white guys like me). I was able to send her the money in 5 seconds using my phone by sending it directly to her phone number through a mobile app.

There has been a revolution in digital money transfer in East Africa since 2007 when the first mobile money app, MPesa was developed in Kenya. It started when a young Kenyan guy had to send money to his ailing mother. At that time, he could only send money through the postal system with a money order but it meant both of them traveling to and from post offices and banks which are often not in remote areas. The other option is to send cash by bus which is a risky prospect. By 2002 mobile phones were pervasive in Africa and this Kenyan guy had a Eureka moment realizing he could send his mother money through his phone by gifting her Airtime (Airtime refers to the credit needed for making calls, sending SMS, and accessing the internet via mobile phone). His mother received, transferred and sold to a neighbour for cash. He realized the best way to transfer money was through the phone and began developing “mobile money.”

Converting digital currency into cash is easy. There are mobile agents everywhere in every village and on any street. Using the app, I can cash out at any of these agents. It means I never have to look for an ATM or carry a credit card. Most street vendors prefer cash so I need to have cash, but I have paid vegetable sellers on the street through M-Pesa when I had no cash. Yes, there are fees for every digital purchase and transfer so the guy who created M-Pesa is a very rich man but the ease with which money flows is a price everyone is willing to pay.

There are no crazy data plans where big communication companies monopolize and gouge users. I buy Airtime through M-Pesa. I buy 50,000 MB of data costing $50 CAN and this lasts anywhere from 4 weeks to 6 weeks. This includes local calls and SMS messages and I use data to call Elizabeth through WhatsApp. I use my phone as a hot spot on and off all day because I have no Wi-Fi at my home and the Wi-Fi at work is intermittent and slow. I can top up anytime and can purchase more Airtime when I need it. No monthly bills with unpleasant surprises. I can look at my app any time and see how much data, SMS and phone minutes I have used. Most people here buy Airtime as they go, purchasing by the week or even the day.

Tanzanians seem more addicted to their phones than Canadians. An in-person conversation gets interrupted at any second with a phone call. People walk around on busy streets looking at their phones. Motorcycle taxi drivers answer phones when driving with mother and child on the back of the bike. I ride my mountain bike through an Agriculture University on the way to the farm and everybody is hooked to their phone, many sitting glued to their screens.

The phone is a tool that keeps families in-touch and drives them apart. A young Tanzania woman told me that the traditional family, with a father controlling what his daughters are allowed to do, has changed because of the smart phone. Traditional fathers would decide what their daughter could do and who she was to marry, but young women now see on their phones through social media apps that there is a wide world of possibility and now they won’t allow their fathers to limit their potential. Yet, there is a great divide between urban and rural norms. Many of the traditional ways are still very present in the regions.

After two decades of sustained growth, Tanzania reached an important milestone in July 2020, when it formally graduated from low-income to lower-middle-income country status. With increased opportunities and subsidized post-secondary education, extended families are dispersed through the entire country. Sons and daughters go to college or university – lives change and the influence of parents diminishes. Family, the core unit of cohesion and culture is quickly changing. Tribal affinities are still alive but it is evident that the attraction to everything available on the world wide web through the phone is disrupting societal bonds.

I work with a brother and sister here – Makyeo and Odillia. Their mother and father live a 10-hour bus ride away and their mother is very sick. Similar to many of us in Canada, we want to care for our parents when they are old but few of us live in the same place we grew up. So, we put them in care homes which makes it easier for us but no parent wants to live in those places – my 92-year-old mother is an example. There are no care homes for the elderly here so Makyeo and Odillia rely on neighbors and relatives to care for their mother. This is a relatively recent change; since time immemorial extended families lived in the same village or region for their whole lives. Video calls on the smart phone cannot replace the care and attention from being at home provides, but visual contact is better than nothing.

Jackie’s mother is home now and healing from her surgery. Jackie is paying me back slowly over time – through M-Pesa. She calls her mother every day and pays as she goes.